Quantum, the industry, is an interesting beast. Just like the scientific theory from which it evolved, the industry is full of perplexing questions and apparent paradoxes.

Why do some people think that quantum tech is underfunded while others are surprised it gets as much funding as it does? Why are quantum companies having trouble hiring, but people who want to get into the industry can’t get jobs? Why do some people say that quantum computers won’t be useful for at least a decade while others say we’re already in the era of quantum advantage?

These apparent paradoxes arise because quantum, the industry, brings together people from all walks of life: academia, software development, design, business, government, and more. It’s a fast-growing industry, but it’s still relatively small and tight-knit. This diversity and closeness leads to remarkable collaboration but it can also lead to tension, as people interpret the world through their own lenses, and then those interpretations clash.

Resolving such paradoxes, therefore, lies in understanding all the players in the ecosystem. Understanding the skills they bring, the challenges they face, the incentive structures in which they operate, and how all of this shapes their world view.

But before we can do that, we need to know who these players are, what role they play, and how they interact. This is the purpose of this post. We’ll also make some progress towards resolving the apparent funding paradox.

A note on tech ecosystems

I usually see people discuss the quantum tech ecosystem in terms of the different kinds of quantum technologies being developed (computing, sensors, cryptography, etc.). This is a really interesting topic and we discuss it in other posts, but here I want to focus on the entities that come together to develop the technologies, rather than the technologies themselves.

I was introduced to this way of thinking in a post on tech ecosystems by Joseph Darko. It’s a great article, with a focus on what makes tech ecosystems healthy. I’ve modified his framework to suit our ecosystem, but I highly recommend reading his original article as well.

The quantum tech ecosystem

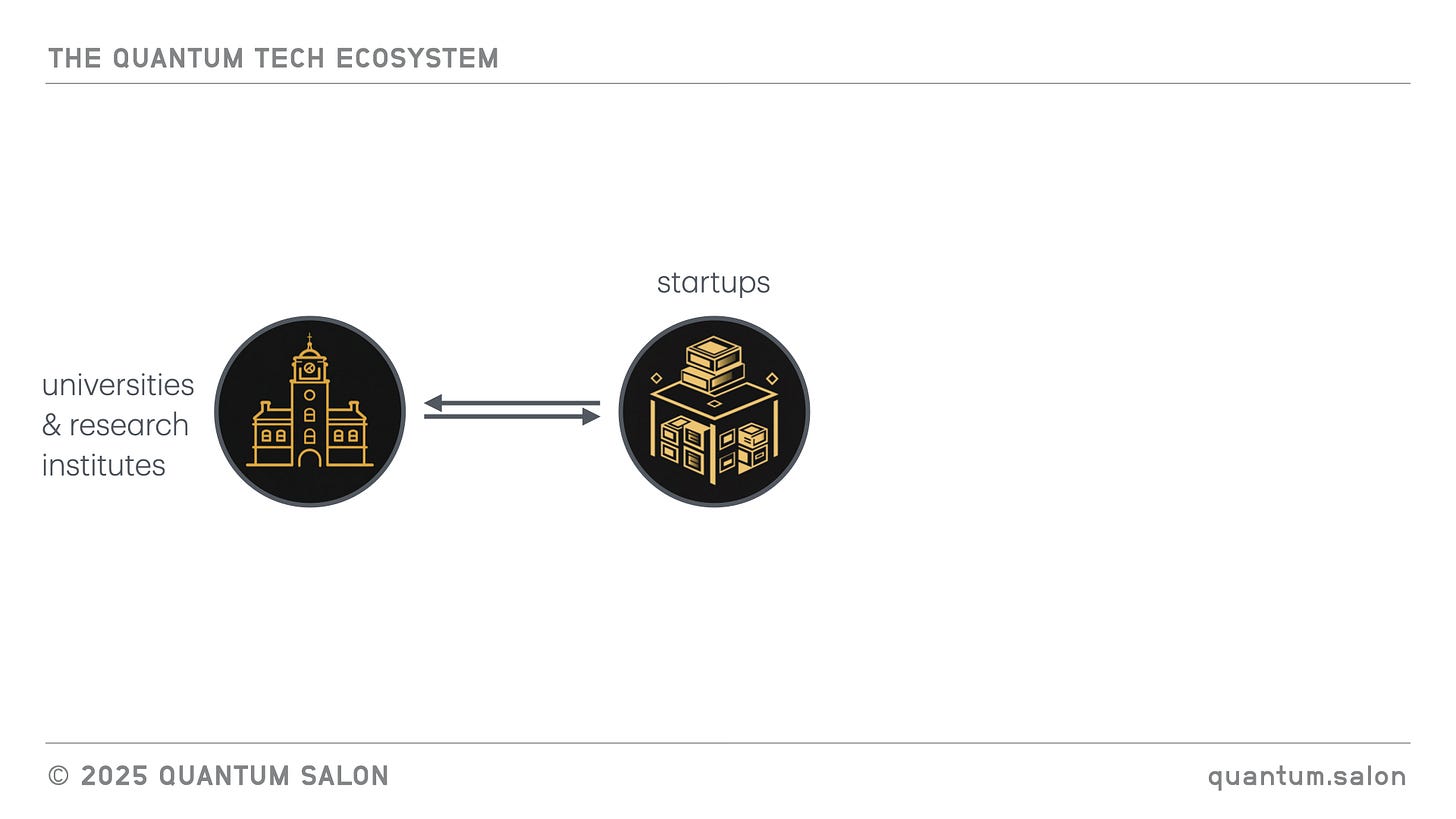

Let’s begin at the source: universities and research institutes. This is where most of the foundational quantum technology starts. It begins as research in a lab. Usually it’s a collaboration between professors, postdocs and students. As the technology matures, the team might get the idea to commercialize it.

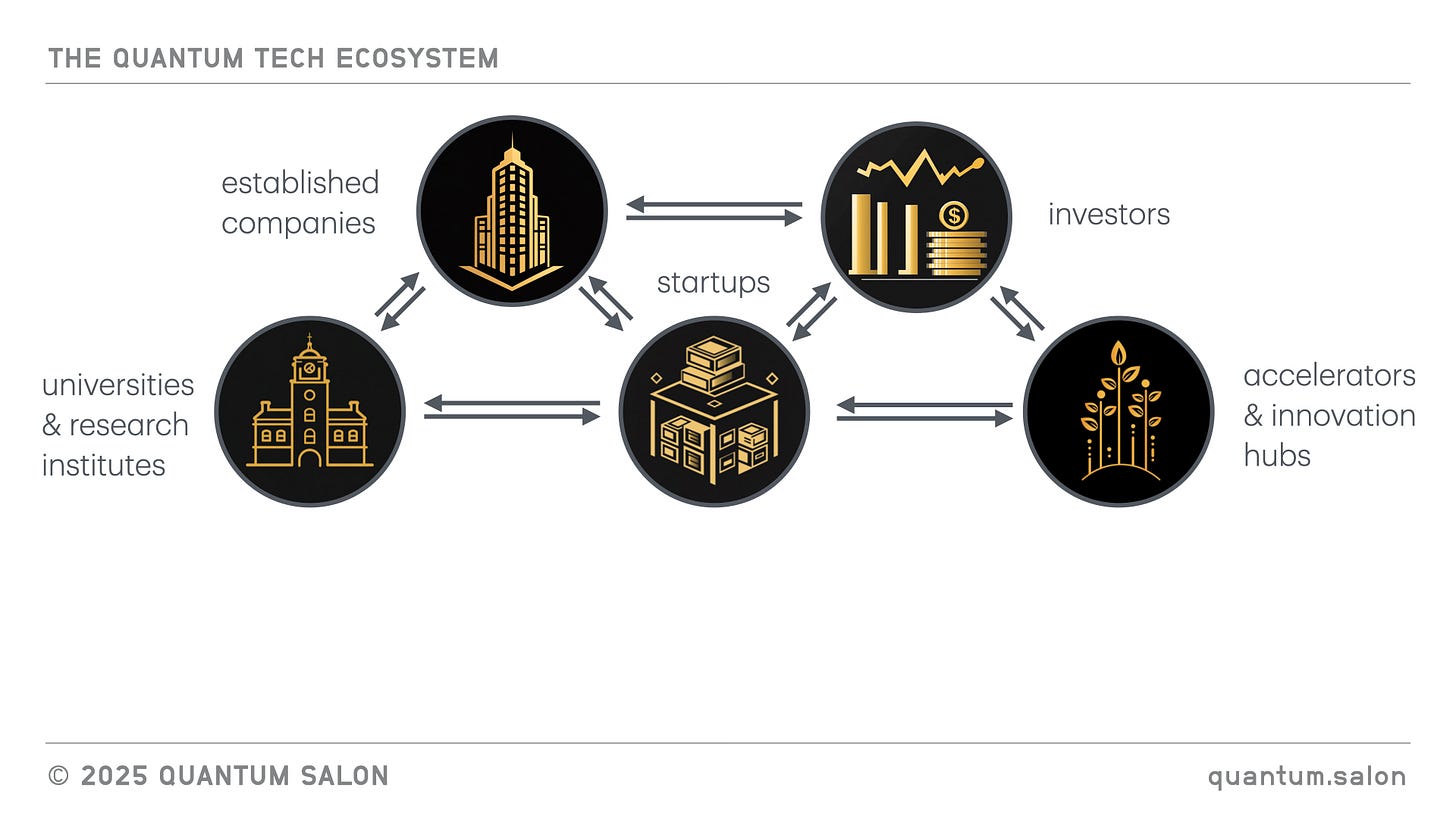

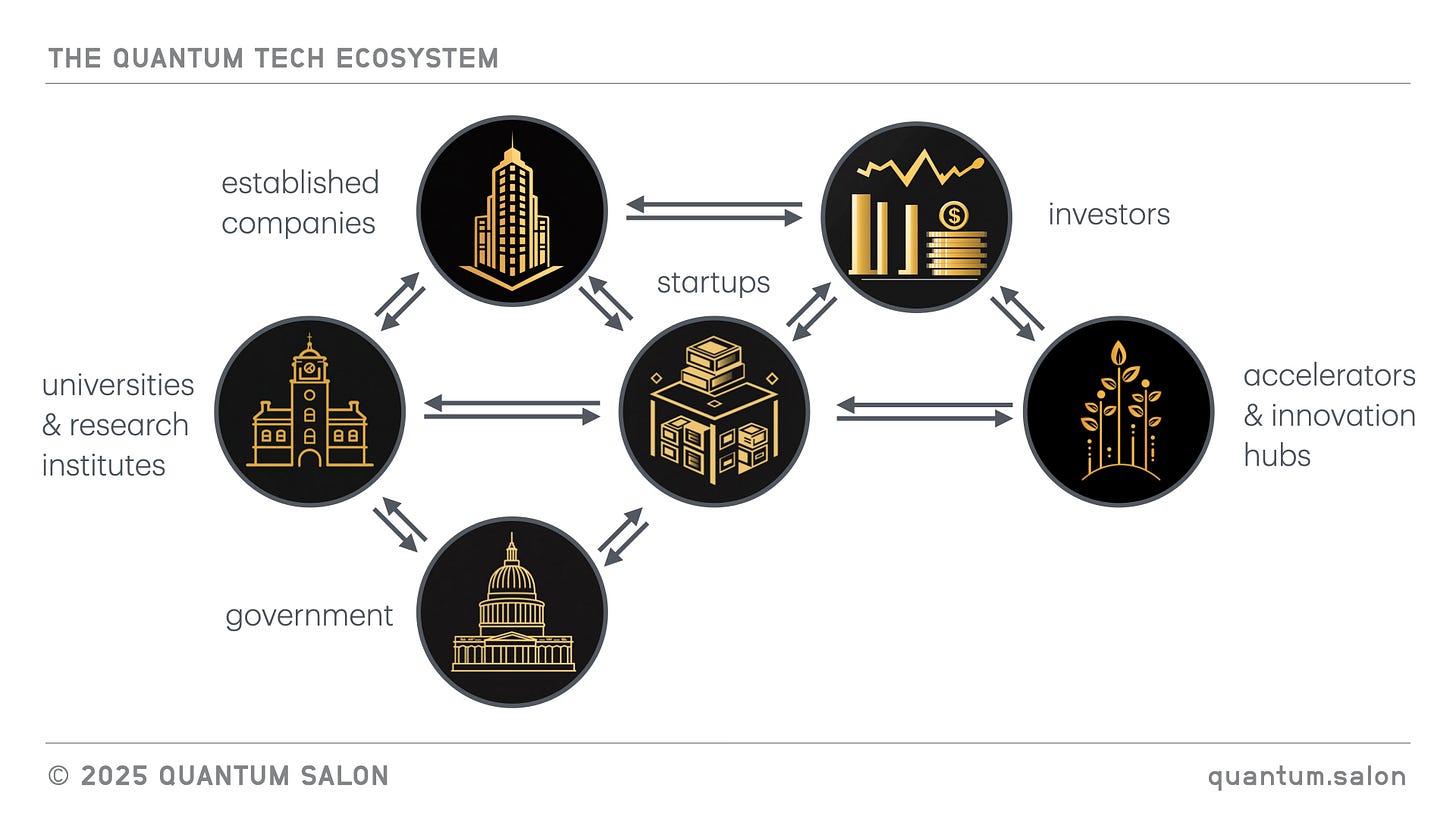

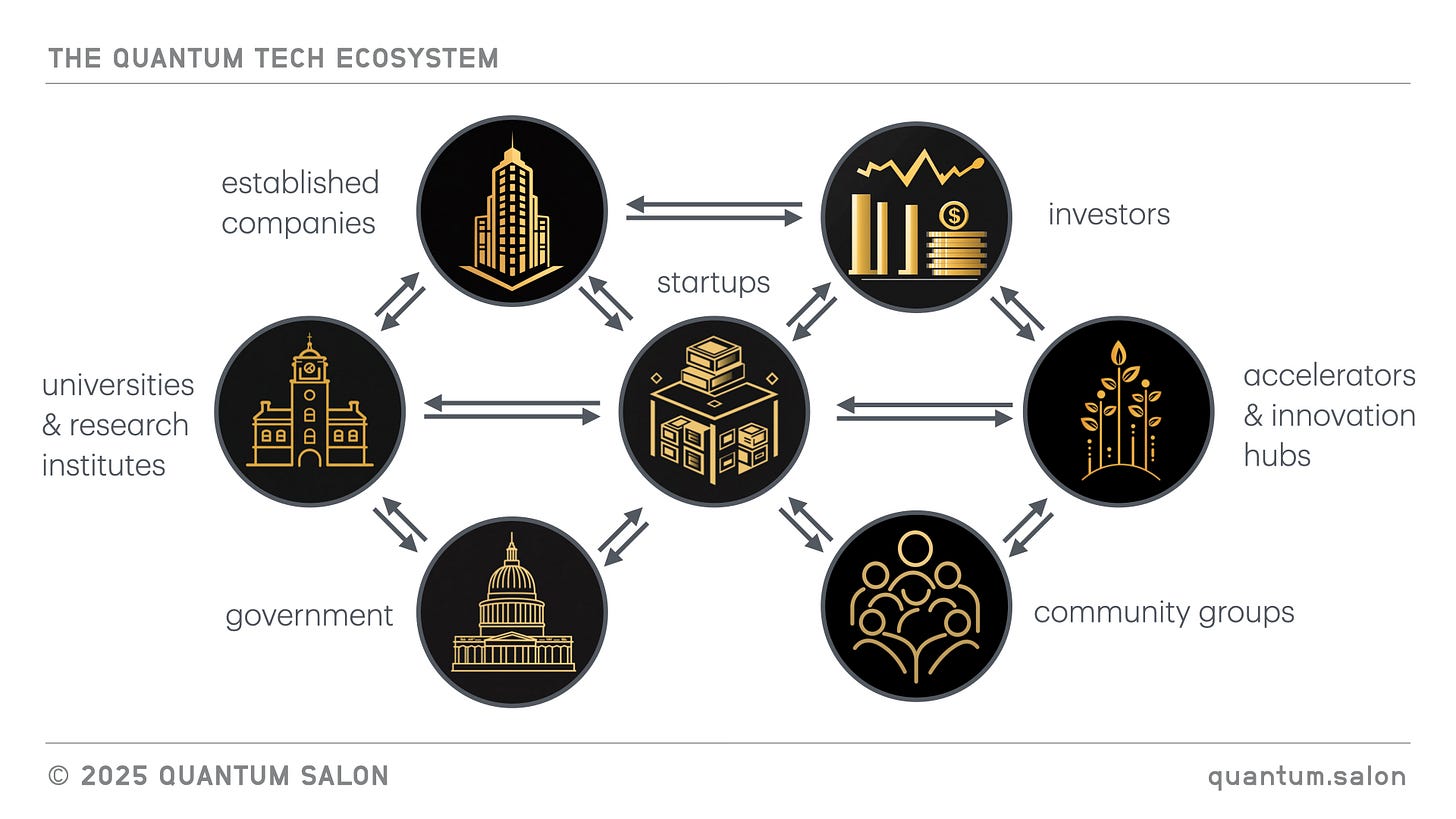

The commercialization process usually takes the form of a startup. Often, there will be relatively tight coupling between the startup and the university, with exchange of resources between the two, as shown in the diagram below.

Intellectual property flows from the universities to the startups, as do people. Universities sometimes also provide lab space during the early stages of company formation. But there’s also a flow of resources from startups back to universities. Startups might sponsor research, provide internships for students, or offer real-world problems for academic researchers to work on.

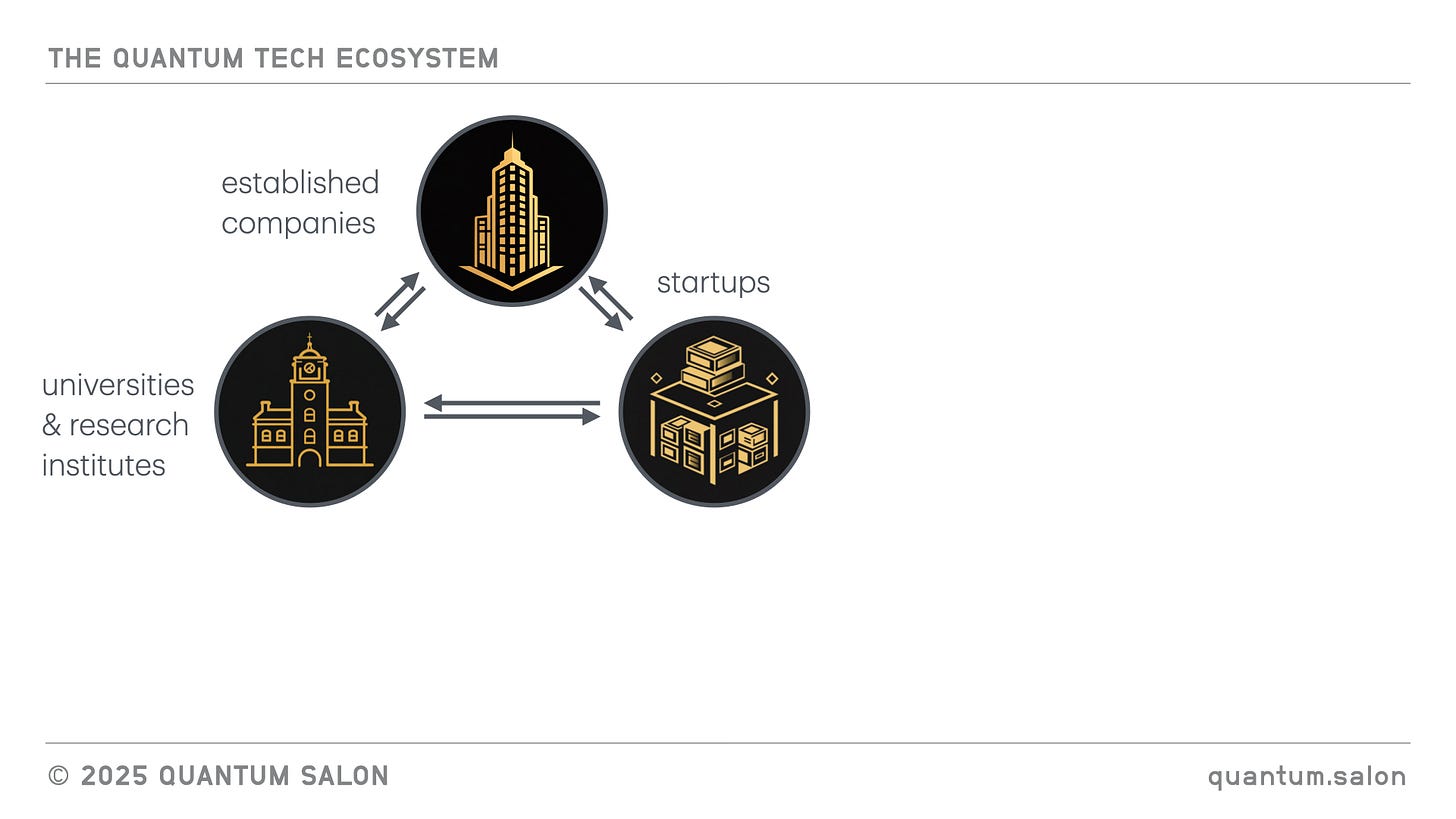

If startups get the chance to grow up, they become established companies. Some established companies conduct their own research & development in quantum tech. But established companies also play a crucial role in the ecosystem that's often underestimated. They provide secure employment for technical people graduating from universities. Without secure and reliable jobs for people after graduation, these graduates might move to other towns or other countries. Established companies are a crucial element in creating a vibrant local tech ecosystem.

Established companies can provide resources and support to startups. Other times they might decide to buy them. Maybe they want the technology that's in the startups, or maybe they want the people. It's actually really difficult to get good people that work well together on a particular area of research, so sometimes established companies see a well-functioning team and decide they would really like to have that team in their company.

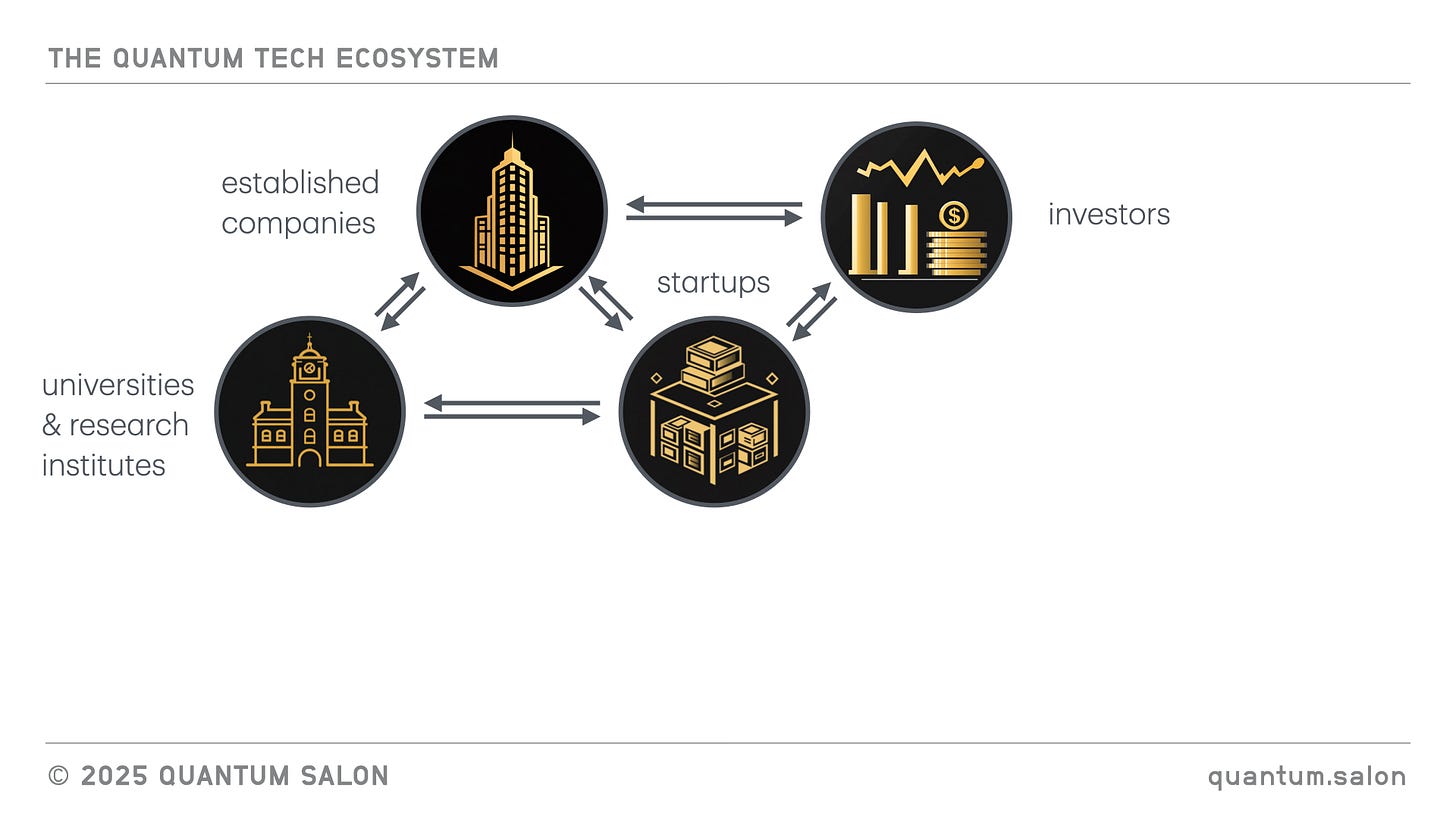

Of course, none of this would be possible without money. So investors are a really important part of the ecosystem. You can have VCs (venture capitalists), private equity firms, or angel investors. These give startups money, which startups need to operate, but in turn the startups provide the investors with opportunities to make more money. This is a symbiotic relationship.

Investors also interact with established companies. They might share information, people might flow between them, and they might support each other in various kinds of partnerships.

Another way that investors support startups is through accelerators and innovation hubs. Accelerators and innovation hubs help startups with funding, infrastructure, mentorship, and access to relevant networks. By supporting accelerators and innovation hubs, investors can find out about the most interesting companies to invest in.

Government also plays an important role. They set the agenda for where the ecosystem should focus, and they do that by deciding where they want to provide funding. They might fund startups in certain ways, they fund universities, they fund certain research programs, and provide tax credits for companies. There is also a flow of people. People who work at universities or other parts of the ecosystem can also go on to become program managers or program directors in government agencies.

And finally, there are community groups. Community groups organize hackathons, meetups, and so on. They add dynamism and provide opportunities for young people to get involved and connected to other parts of the ecosystem.

The quantum tech ecosystem is an interconnected and interdependent network of diverse entities coming together to spur innovation in quantum technologies. As with ecological ecosystems, each entity is needed for the quantum tech ecosystem to thrive.

Side bar: If you prefer video, you can watch me discuss the quantum tech ecosystem here, through the lens of careers in quantum.

Resolving the funding paradox

With this framework in place, let’s take a look at the question of funding, and why some people think it's too much and others think it's not enough.

Funding in academia is a scarce resource and the competition for that limited funding is fierce. The amount of funding that many academics see is quite small compared to the money that gets passed around in industry and the startup world.

Academics are also a lot closer to the science and technology. They have a really good sense of what it takes to develop the technology, and they have a really good sense of the state of the art. When they read claims in non-academic outlets, about what quantum tech is supposed to achieve, they interpret it through their technical lens, and see it as hype.

Now let’s take a look at established companies. When established companies invest in R&D, it isn’t usually about immediate financial returns. It's about positioning themselves for potential future advantages and signalling innovation to customers, partners, investors, and potential future hires. Being seen at the forefront of emerging technologies can be valuable beyond immediate returns.

What about investors? Most investors invest in many different kinds of technologies, not just quantum. VCs typically bet that most of their investments will fail, but a few will succeed so dramatically that they more than make up for the other failures. By design, their portfolios contain companies with different levels of risk and different expectations of reward (ideally reward and risk are correlated, but not always). Quantum companies might be high risk, but they sit alongside other companies whose risk is lower.

So from an academic’s perspective, quantum is getting so much more money than similar-but-not-quantum areas of research, and the technological challenges are enormous. They therefore think that putting this much money into a technology that is far from mature is incredibly risky. On the other hand, from the perspective of enterprise companies and investors who are investing in multiple innovative technologies as a whole, the amount of money being put into quantum is relatively small (say when compared with AI), and it’s part of a larger diversified risk portfolio anyway.

What about government? Governments are interested in more than just the technology. They are interested in creating vibrant technology ecosystems in order to grow the economy, create jobs, and make them competitive against other countries. So one of the ways they prioritize funding is in favour of technologies where there’s a good chance that all of the pieces can come together into a vibrant ecosystem.

Quantum has a certain je ne sais quoi, which makes people want to get involved in it. This generates momentum, making it an attractive ecosystem for governments to invest in. Even if some specific technologies don't work out as planned, the ecosystem will still have value because it can be leveraged in other ways. Incidentally, this is why you see so much news about new partnerships being formed. Governments like to see partnerships as evidence that the ecosystem is functioning well.

Different governments likely differ on whether they think quantum is under- or over-funded, but whatever side they land on will depend on more than just the viability of specific pieces of technology.

Looking forward

As it always turns out, there are no quantum paradoxes. You just need the right framework to see the different perspectives. This is true in quantum theory and it’s true in the quantum ecosystem.

For the question of over- vs. under-funding, it depends on which lens you’re viewing the situation through. But it also raises another question of whether it’s possible to make a global statement about the right level of funding, a statement that takes the whole ecosystem into account. That’s an interesting question. One I don’t have the answer to, but might get a chance to explore someday.

In future posts, I plan to cover the other apparent paradoxes mentioned in the introduction, as well as any others that come up. I also plan to dive deeper into how different players in the ecosystem see their roles, and how this influences how they act. In the mean time, I hope this framework will help you answer some of your own questions.

Finally, this framework is a work-in-progress, so if you think there are some pieces missing, or you’d like to suggest some other modifications, I would love to hear from you.

We believe that effective communication starts with understanding your audience. If you’d like to chat about what that means for you, get in touch at Quantum Salon.